What I Learned In 1 Year At Twitter

What went well, didn't go well and how I learned from my experience.

|

A year ago, I joined Twitter as a software engineer in the Ads Measurement team after interviewing with many top tech companies in the Seattle region. You can read more about my story here.

In my mind, I had a checklist of what I was looking for. It was organized in descending priority:

- A supportive team that works as a unit

- Work-life balance

- Financial compensation at market value

- The company supports and provides ample opportunities for employees to learn and grow

- The company is accelerating in growth

I had the privilege of choosing from many top-tier tech companies at the time. After evaluating all options and discussing with my friends and family, I decided to join Twitter.

This article is a condensation of my thoughts after a year at Twitter, what I learned as a software engineer, how I spent my time, and much more. More than anything, this is a self-reflection to keep myself accountable for my own career and decisions.

What I’ve learned in the past year

Strong engineering culture ensures excellence

As an engineer, I’ve witnessed first-hand that Twitter has a strong engineering culture that pushes engineers to settle for nothing less than excellence. Twitter is intensely focused on promoting a growth mindset — so much so that they send over a book called Mindset on a new hire’s first day of work. And since we’re a Scala-heavy team, there’s also a copy of Scala for the Impatient 🙂

Recommended Reading for new hires

Other than that, I’ve also observed some key areas where Twitter places emphasis on excellent engineering culture.

Move fast, break things.

There’s a caveat with the motto, however — who will fix the broken things? During my time at Twitter, I’ve learned that the culture of moving fast needs to be accompanied with appropriate metrics and alerting to help you monitor progress.

Coming from a startup background, the top priority was to ship things. Features make money, code quality doesn’t. Yet many software engineers will tell you that the majority of the cost in software development comes from the long-term maintenance of the software. The trade-off between shipping fast and shipping with quality is often a topic of debate.

What I’ve learned is that shipping with high velocity is fine as long as there are proper metrics and strategies to limit blast radius*.*

Proper alerts and metrics in-place can help you monitor the health of your feature, and inform the decision of “should I keep or kill this feature?” Being able to limit blast radius means you can experiment freely with new features while being able to isolate the scope of impact. Both together will truly allow you to “move fast and break things”.

Process is crucial in a big team

Process helps build consistency, and enables new engineers to onboard quickly. In a small startup of 50–100 people, it can be easy to mentor and onboard a new hire. However, once a company size hits a certain threshold, it becomes hard to keep track of things without standard procedure. Furthermore, the difficult to share knowledge grows exponentially with large groups of people.

There’s a lot of talk about process as “bureaucracy”, “low productivity”, “necessary evil” and so forth. In some ways, that is true. On the flip side, I’ve seen first-hand how processes build consistency, reduce complexity, and increase productivity. Processes are guidelines — not rules — and can be updated as the team/company grows.

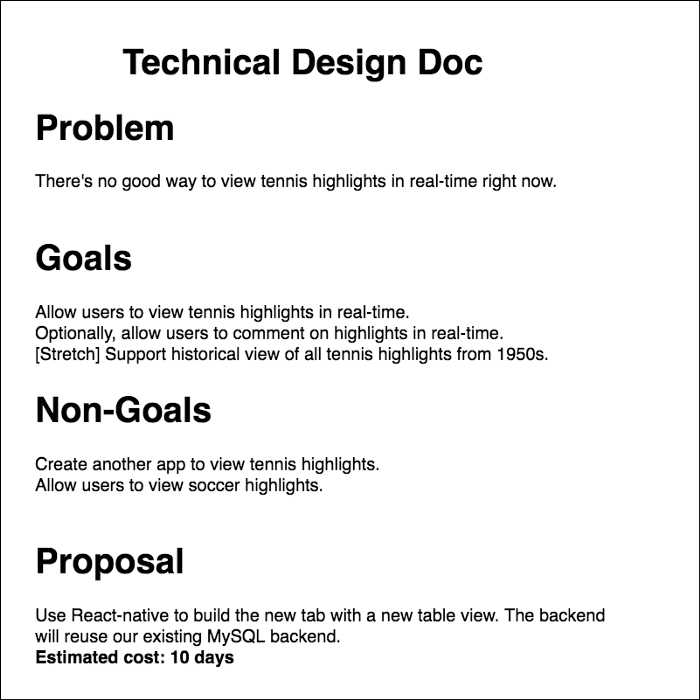

For example, every new project is accompanied by a technical design document that outlines the goal(s), non-goal(s), possible solutions, success criteria, and potential risk factors.

Internally, we wrote a template for our technical design doc to standardize the design process. The template itself forces the lead engineer to think about entire end-to-end scenarios, from deriving requirements, considering pros and cons of various alternatives, picking a solution, and then tying back the solution into success criteria.

Using data as a success metric allows us to move fast and/or pivot in case things don’t work out.

In addition, we have our work planned out in 2-week sprints, and we have a retrospective at the end of every sprint. Each sprint begins with a list of tasks that are prioritized according to resource availability and urgency. We then put these tasks into a Google spreadsheet, which is then populated like a calendar. I think it works amazingly well for keeping track of tasks, identifying bottlenecks, and most importantly, figuring out if we can deliver all tasks on time.

At the end of every sprint, we have a retrospective that discusses what went well and what could be improved. The retrospective celebrates wins and highlights failures so that we can learn from them to avoid making the same mistakes in the future.

It’s important to celebrate wins, such as shipping a new product and reducing tech debt, because everyone worked really hard to achieve these. Morale is critical to keeping momentum high in the team. On the other hand, it’s also equally useful to scrutinize mess-ups so that we can identify what went wrong. There’s a right and wrong way of scrutinizing mistakes, which brings me to my next observation.

Blameless culture

Twitter encourages a blame-less environment, which further promotes learning from mistakes rather than finding fault. Mistakes happen to the best of us, and it’s important to have a healthy culture around failures.

I’m not saying that we should just forgive and forget. Rather, we should vigorously search for the root cause, so that we can fix it at the core and prevent shooting ourselves in the foot in the future.

Will Smith famously said in this interview:

“The best things in life are on the other side of fear.”

I believe that making mistakes and taking risks are critical to building a resilient, fast-moving company. Thus, it’s very important to me as an engineer that the company I’m working for allows me to do just that. And Twitter has done exactly that — supported me by giving me the opportunity to take risks, make mistakes, and learn from them.

I’ve had my own share of failures in the past year. I dealt with them by coming up with a post-mortem analyzing what went wrong, why it happened, how it happened, and what could be done better next time around. The focus here is to pick apart what caused the issue and what barriers we can put in place to prevent similar blunders moving forward.

Focusing on quality pays interest

Like any other tech company, Twitter has tech debt that lurks around the corner just waiting to pounce. It’s like the elephant in the room — people notice it, yet they choose to ignore it. That is, until the elephant rears its massive, powerful trunk and crashes the party.

We recently started this hashtag, #CoreQuality, (we have a culture of making hashtags for everything) to reinforce internally what we are focusing on for the quarter. That’s right — we spent a quarter working on cleaning up code (a.k.a code refactoring), paying off tech debt, writing documentation, and investing in long-term stability.

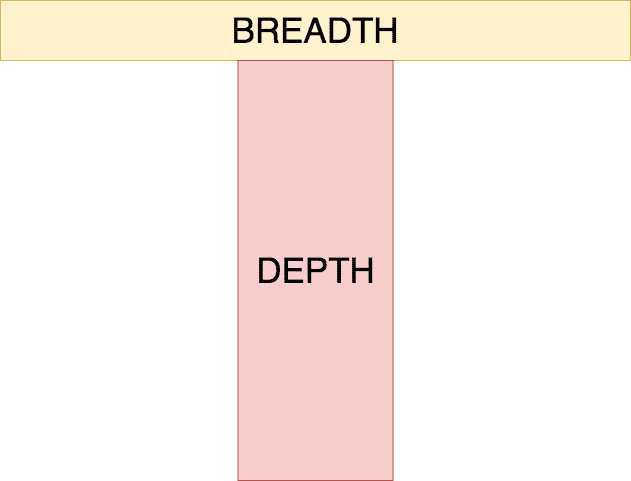

Along with #CoreQuality, we identified that spreading knowledge around the team is a critical step towards long-term stability. The way we thought about it was building up a T-shaped knowledge graph:

A T-shaped knowledge has 2 components:

- Breadth, or “what do you know?”

- Depth, or “how well do you know it?”

We had realized at some point that some team members had deep expertise in a specific service while having basically zero knowledge of anything outside.

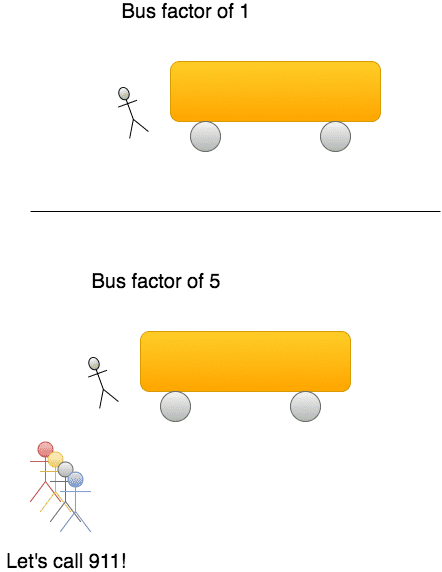

This is so common that there’s a term for it — bus factor. It’s the risk factor of the number of team members that need to disappear before the project halts due to lack of expertise. A bus factor of 1 can also be loosely understood as a single point of failure, meaning that if this one key expert disappears, then the project will fail.

Our goal is to eliminate a bus factor of 1 across the team. To that end, we had started multiple initiatives:

- Invest 30 minutes every day on documentation (thanks to Open source portfolio). Our teammate, Lenny, suggested that we build up a habit of writing things we learn throughout the day, 30 minutes at a time.

- Encourage tech brown bags. A brown bag is essentially a lunch presentation where a team member shares their expertise with the rest of the team. We have had talks on Scalding, Summingbird, and Hadoop Map-Reduce during lunch from our local experts. It’s also a great opportunity to learn tech stacks that you might not have known otherwise.

- Assign tasks outside of domain of expertise every sprint. Everyone is assigned a different task each sprint, giving the opportunity to learn a different tech stack or code base. I personally find this to be a very effective way of spreading knowledge, because I wouldn’t be able to dive into another code base otherwise.

Team is much more important than project

The people you work with on a day-to-day basis make a much bigger impact on your career than a project or company.

A great team makes down times bearable, and up times exhilarating.

Projects come and go, but teams stay together even after a project is dissolved or shipped. If you’re spending eight hours a day together, wouldn’t you much prefer to work with people you like?

In my past year, being able to work together with a team of rockstars has been fun, challenging, exciting, and refreshing all at the same time. When everyone in your team is a rockstar, they motivate you to succeed just as much as you motivate them. We push and hold each other to a high bar. We work hard, and we play just as hard.

The best people own problems

Opportunities arise in dangerous situations, and that’s when you see the best people step up to the moment and seize it. Being at Twitter in the midst of the the turnaround has given me a rare opportunity to take a glimpse at some of the many problems within the organization.

“The Chinese use two brush strokes to write the word ‘crisis.’ One brush stroke stands for danger; the other for opportunity.” — J.F. Kennedy

The best people tend to own, rather than point out, problems. They’re quick to sniff out issues before everyone else does, and they’re always one of the first to volunteer to fix them.

Twitter is a very small company relative to the scope and impact it makes in the world. The small size makes it easy for small teams to make outsized impact. It is not uncommon to see a team of 10 run an operation that is helping generate tens of millions of dollars per annum for the company.

In a way, that’s what makes working at Twitter very special: the opportunity to own problems and fix them.

As I mentioned earlier, one of my criteria for picking a company is that the company needs to support and provide ample opportunities for employees to learn and grow. And I’ve found that this is truly the case for me here. Taking ownership of problems, even those that are beyond my pay-grade, allows me to challenge and stretch myself to the limits.

Was joining Twitter the right decision?

Ultimately, this is the question to ask after a year-long stint. In short, it’s a definite, resounding yes — I love the team I work with, the scope and impact I have, the opportunities to grow, and much, much more. Again, here is the checklist I had:

- A supportive team that works as a unit

- Work-life balance

- Financial compensation is at market value

- The company supports and provides ample opportunities for employees to learn and grow

- The company is accelerating in growth

The work-life balance at Twitter depends a lot on how you operate. I often work 9–5 on weekdays, and sometimes on weekends just because I want to, not because I need to. When I’m working on a feature I’m really excited about, it doesn’t feel like work anyway.

We have also recently started No-Meeting on Tuesdays and Thursdays across the organization, so that we’re not bounded by meetings and can focus on execution instead.

From a financial compensation point of view, Twitter tries to do right by its employees with stock refreshers, competitive salary, generous RSUs, 401K and more. It also helps inspire retention now that Twitter has almost 3x in valuation since the time I joined.